H5/6. Very Tough Hardy hybrids, some species & dwarfs, yak hybrids and most evergreen and deciduous azaleas. Anyone who lives high up or in inland valleys: Scotland's Clyde, Earn, Tay, Dee, Don valleys should concentrate on these varieties with some H4s. H5 areas tend to have late frosts, so choose mostly varieties which flower May-June to avoid losing flowers. Suitable for Germany, Denmark, S Sweden.

H4 Hardy Glendoick, Perth, Dundee, Coastal Fife, Edinburgh, Most of England, Coastal Norway, Belgium etc, not too far from the sea. With plenty of shelter inland, in a woodland garden, or on slope with good frost drainage. Lots of hybrids and species are H4.

H3. Moderately Hardy Glendoick in sheltered woodland site, or with some protection in cold winters. Coastal England and Wales, France, Spain, Italy. May suffer damage in severe winters or bark split from late frosts. Many big leaved species are H3.

H2 Tender. Indoors on east coast, fine outdoors in Cornwall, Ireland, Argyll and similar gulf-stream mild climates. Scented Section Maddenia species for conservatory/greenhouse.

H1 Indoors (frost free) only. This is for Vireyas (tropical species)

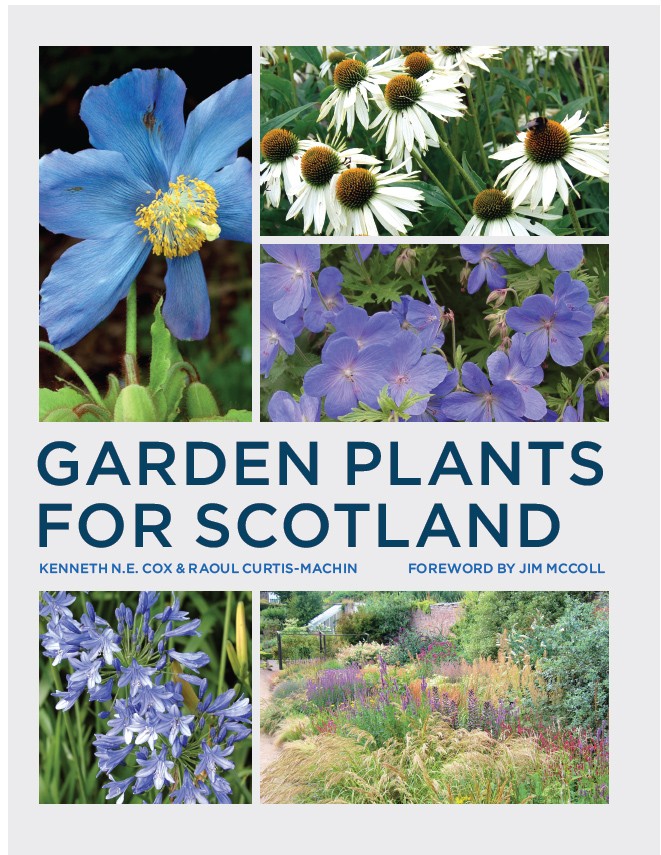

Adapted from Garden Plants for Scotland by Kenneth Cox and Raoul Curtis Machin

Late December 2009 and early 2010 and then again in December 2010 saw the whole of the UK hit with the coldest temperatures seen for 30 years. Sustained cold saw temperatures hit -10C to -18C for several nights in many inland areas and for temperatures to remain below freezing for many consecutive days and nights.

Many evergreen plants were desiccated, damaged or completely killed by this weather. Dermot Gavin's olive-and-agave-filled gardens may well be no more. Particularly vulnerable will be plants in containers which may well have had their roots completely killed. But do not be too quick to assume the worst. Snow cover is the best insulator against extreme cold and even if the top of your plants look dead, there is every chance they they will break from below. Most perennials will probably be fine. My advice would be to leave most plants in the ground for at least 6 months before you give up. For plants in containers you'll know the outcome more quickly, you will be able to look for signs of live roots in March and April. Sometimes container plants will start growing only to collapse in early Spring. If roots are all black or brown, then chances are that your plant is a goner. Camellia, Magnolia, Laurels and Photina ‘Red Robin' are all plants particularly vulnerable to having their roots killed in containers.

At Glendoick, after the very hard 1980-81 winter many plants such as Pieris and Crinodendron were defoliated and looked stone dead. But in the Spring young growth reappeared and once we cut the dead shoots away, all was well. 30 years on you'd never have known there was any damage.

Plants killed or severely damaged at Glendoick in December 2009-January/February 2010 and/or November-December 2010

In the ground: All Ceanothus, Crinodendron, Abutilon, some Eucalyptus, A few Maddenia rhododendrons, Hebe, Cistus, Rosmarinus, Olearia Henry Travers, Hoheria sexsylosa 'Stardust' and 'Glory of Amwych', Eucryphia lucida, Cupressyparis x Castlewellan Gold, Coprosma.

In pots, most of the above plus: Skimmia, Camellia, Ceanothus, Phormium, Cordyline, laurels,

Come the Spring, the question is, what to replant? Bar in mind that such winters come along every 30 years or so. So there is every chance that that's it for many years. Or perhaps it will happen again next winter. All gardening involves a little gambling. The best source of advice is the book Garden Plants for Scotland which tries to give an honest and the list of Scottish Gardenplant award plants with an H5 rating. These are the tried and tested toughest plants rated for Scotland.

Many rhododendrons will have burned leaves and lost flower buds after the big freeze, but most will probably recover and grow away in the Spring. Those least likely to remover are some of the more tender large-leaved species such as R. sinogrande and smooth barked species such as R. griffithianum. Amongst those vest at regeneration after a freeze are R. arboreum and R. macabeanum. If in doubt, leave them alone and wait and see. If there is no sign of growth by June, you probably need to dig the plant out.

From Garden Plants for Scotland, Ken Cox & Raoul Curtis Machin

There is much more to hardiness than minimum temperatures. Cold is traditionally perceived to be the biggest killer of plants, but in Scotland poor drainage and cold winds are just as likely to be the cause of failure. So just because a plant is rated as very hardy (H5) does not mean that it will always survive in cold waterlogged soil or in a very windy place. Cold damage does not simply depend on how cold it gets. Just as important is the timing and length of the cold spell and whether plants are in growth, coming into growth, slowing down or fully hardened off. The good thing about the big freeze of 2009-10 is that it came in mid winter after plants were well hardened off. And the snow cover was another godsend. The worst damage tends to occur in late Spring when plants are in young growth or after early hard frosts when plants are still growing happily, oblivious of the cold blast about to thump them. Many plants come from countries with more clearly defined and consistent seasons - regularly hot summers and cold winters, for example - but unfortunately, Britain's seasons are more vague and fickle. Winter and spring are stop-start: one minute it's mild and moist and buds are opening, and the next it's sharp and frosty. Heavy snow can appear overnight, only to turn to slush twenty-four hours later. In general, plants like to rest in winter. Think of the alpine saxifrage, clinging to a ledge on the side of a mountain, happily asleep under a thick duvet of snow that appeared in November and won't leave until spring; all growth has stopped, and resources are conserved for the following year's efforts. No such luck for the garden saxifrage in Scotland, where the fluctuating temperatures trick the plant into thinking that it's spring, only for the cold to return again days later. Likewise plants found in Mediterranean regions, such as lavender, are able to withstand winter chills, but their native winters are usually drier than in Scotland: they don't get prolonged periods of damp cold. The fungal diseases and dieback often seen on older lavender plants in Scotlandare partly the result of the humidity of our winters and springs. Plants are 90 per cent water and frost damage takes place when the water in soft (growing or not hardened-off) plant tissue freezes, rupturing cells in leaves, stems and flowers. As soon as the plant thaws out, the damaged tissue turns to mush. Damage can be above ground or below. A heavy frost can penetrate the soil down to a hand's depth - enough to freeze the moisture in plant roots - and this can be fatal to many tender plants such as dahlia tubers.

Frost damage can be reduced or prevented by protective coverings such as fleece, and cloches are perfect for alpines and small bulbs. Bubble wrap or another insulating material might not look the prettiest addition to the garden, but it might save the life of a cherished plant. Mature tree ferns (Dicksonia antarctica) can thrive in some cold corners of our country with their trunks tied up with bubble wrap in winter. The huge-leaved Gunnera manicata has a frost-sensitive crown, which can easily be protected by piling some of its old leaves on top. Such techniques can also help many young plants to get established: a mulch of compost or well-rotted organic matter will not only protect the crowns of plants such as Stokesia, Delphinium, Imperata andKniphofia in winter but also provide nourishment during the following growing season.

A good precautionary measure for borderline-hardy plants is to take cuttings in summer and early autumn. This works well for plants such as Penstemon, Fuchsia and Helianthemum, which can be killed off during a severe winter.

What should you do if you garden in these areas to reduce the ill effects of frost and cold? Place your early flowering and growing plants in the most favourable sites in the garden - against and beside west- and south-facing walls, for instance. Keep a roll of white spun polypropylene (horticultural fleece) handy for covering plants, and don't be tempted to plant out bedding and other tender plants until mid or late May unless you can cover them up. Young plants are particularly vulnerable to unseasonal or sudden frosts, as freezing sap may rupture the main stem and kill the plant; as the plant matures a woody trunk or stem is produced and the damage becomes more cosmetic, and new growth is usually produced below the damage. Repeated spring frosts on shrubs such as Hydrangea macrophylla are seldom fatal, but they can reduce or prevent flowering to such an extent that the shrubs don't earn their keep in your garden.

The areas worst affected by regular frosts during the early part of the growing season are known as frost pockets. The valley bottom can be as much as 8¢ªC colder at dawn (the coldest time) than land at 200m up the surrounding hillsides, where frost drains readily down the slopes. Inland river valleys are Scotland's severest frost pockets: the Tweed valley and its tributaries (one of the coldest areas of Scotland), the Forth/M8 corridor, Lanarkshire and the Clyde valley, the Earn valley, Strathmore, the Dee and Don valleys and the Spey valley are all examples of places where late frosts are relatively common. Those who garden in frost pockets might be advised to stick largely to H5 plants (see hardiness ratings), and they may have to wait till late May/early June before putting out tender bedding. Those who garden on the slopes above a river may escape damage, as the frost is likely to drain away, while those who garden by the river itself are usually the worst affected. Those at higher altitudes may, of course, have other problems such as strong winds and more persistent snow to contend with.

Micro-climate: ‘Local conditions of shade, exposure, wind, drainage and other factors that affect plant growth at any particular site. Gardeners take advantage of microclimates to grow plants that would otherwise not succeed in their general area.' (Taylor's Dictionary for Gardeners, 1997)

Microclimates, or variations in climate within an area, can occur because of various natural geographical influences such as water, shelter, slope or aspect, as well as man-made intervention. In cities and towns the local climate is influenced by what is known as the ‘heat island effect': the cumulative heat escaping from buildings artificially raises the temperature, making it higher than the rural equivalent. Microclimates can also occur within gardens, even very small ones, and they can be created and manipulated by changing the garden's structure and planting. A bed or border right beside a house will be warmer and more sheltered than ones in the open or away from heated buildings. South-facing walls are consistently warmer than other walls because they soak up the sun's warmth for the longest daytime period and then slowly reflect this heat back. Old stone and brick absorb and radiate more heat than other materials, acting like storage heaters. White paints and renders will reflect heat and light too, which helps plants to ripen wood.

Walled gardens provide a particularly good opportunity to exploit differences in microclimate. Each aspect provides differing light and temperature, with north walls being the coldest - but also places where plants are the latest into growth - and showing the smallest temperature fluctuations. East-facing walls catch early morning sun, which can damage frozen leaves or flowers on shrubs such as camellias, while west-facing walls are warm but often catch the prevailing winds. The high walls of many town gardens present opportunities for walled gardens in miniature, with walls facing different directions providing support and shelter for different plants.

Large bodies of water - both the sea and nearby rivers or lochs - have a warming influence in winter and a cooling effect in summer, because the temperature of the water does not drop or heat up as quickly as that of the land. The wide expanses of water in the river estuaries of the Forth, Tay, and Moray Firths have a benign influence on the winter climate. The influence of the Gulf Stream on Scotland's climate, mentioned above, allows gardeners in parts of the Western Isles and the west coast to grow all sorts of exotics, not normally hardy at such northerly latitudes.

Where and how a plant has been grown before going on sale plays an important role in its subsequent hardiness. Many garden-centre plants are grown in large commercial nurseries, where they are often mollycoddled in comfortable heated greenhouses and tunnels, sheltered from wind, their roots happily feasting on perfect compost mixtures. Plants grown in tunnels often have their growth inappropriately advanced for the outside world, and if stock is brought north, this problem can be even more pronounced. In colder parts of Scotland and northern England, new growth and flowering in the spring can be a month or more behind the south of England. Plants with advanced growth should be gradually hardened off - that is, placed outside in the spring daytime and then brought under cover (usually a greenhouse or cold frame) at night if frost is forecast] or if planted outside, then covered with fleece if nights are cold . Herbs are one example of a plant which is commonly forced in tunnels and brought to Scotland far too early in the year to be planted out unprotected. We would not recommend planting them out until May at the earliest and June in coldest inland areas. The most vulnerable of all are most bedding plants, which are unable to withstand cold temperatures. They can be knocked back for months or killed when they are planted outdoors too early. That tempting Osteospermum might look lovely flowering away on the sales bench, but in Scotland it is June before the weather warms up sufficiently to keep them going.

H5/6. Very Tough. Suitable for any Scottish Garden

H4 Hardy Suitable for most Scottish gardens but may be damaged in most severe winters.

H3. Moderately Hardy. Sheltered or coastal gardens. May be killed in hardest winters.

H2 Tender, hardy outdoors on west coast.

H1 Indoors (frost free) only.